On December 27, 1953, Ruth Bader and Martin “Marty” Ginsburg held an engagement party at the Plaza Hotel in New York City. A professional photographer captured the 20-year-old dark blonde in a blue off-the-shoulder tea dress. Her friends described her as looking “radiant.”

The party venue inside the hotel was the Persian Room, an Art Deco-style nightclub with a 27-foot bar that opened in 1934. In the 1950s, the Persian Room was graced by some of the era’s most prominent entertainers—both Miles Davis and Duke Ellington recorded live records there in 1958—but its real attraction was the dance floor. And Ruth loved to dance.

The young couple’s wedding six months later was, by comparison, vastly subdued, and the total antithesis of weddings at the time, which trended toward extravagant as the economy recovered in the aftermath of World War II. Hollywood also played a significant role in influencing brides to go all out. In 1950, the original Father of the Bride was released. The film was a celebration of the big wedding in all its glory, in the trope of the high-maintenance bride, played by Elizabeth Taylor, who turns her every wish over to her money-worried father, played by Spencer Tracy. It was a box-office smash.

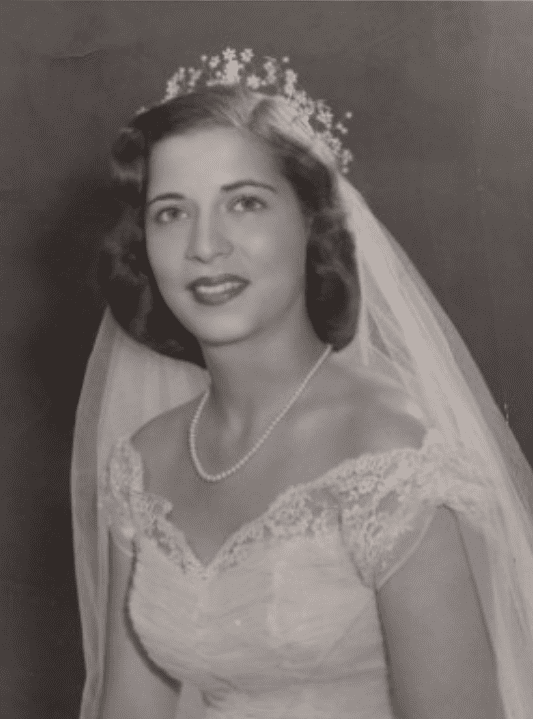

Instead of an OTT affair—which they could afford with the help of Marty’s parents—Ruth and Marty said their vows on June 23, 1954 in the wood-paneled living room of Marty’s parents’ house on Long Island. Eighteen family members were in attendance. Ruth wore an off-the-shoulder lace gown and a pearl necklace, a delicate flower crown anchoring her veil. The bridal party was an impromptu party of one: Marty’s younger sister, Claire, trailed Ruth down the stairs and stood next to her under the chuppah, or wedding canopy, which was placed in front of the fireplace. They held what we now call, of course, an “intimate ceremony,” which they chose for the most practical of reasons: to save money on wedding costs, writes Jane Sherron De Hart, author of Ruth Bader Ginsburg: A Life.

Their intimate wedding served as the quiet and practical spark to a long, extraordinary union. On their wedding day, Evelyn, Marty’s mother, had taken Ruth aside and handed her a pair of earplugs while delivering the secret to a happy marriage: “In every good marriage, it pays sometimes to be a little deaf.”

“I have followed that advice assiduously, and not only at home through 56 years of a marital partnership nonpareil,” Ruth recalled in 2016. “I have employed it as well in every workplace, including the Supreme Court.”

That summer day in 1954, Ruth and Marty didn’t just establish a marriage—they established a partnership centered on support and equality, one that bolstered Ruth’s every career move on the way to her U.S. Supreme Court nomination some 40 years later.

While both were studying law at Harvard in the late 1950s, Marty was diagnosed with testicular cancer. Ruth attended classes for him, took notes, and typed them up while raising their daughter, Jane, and working toward becoming the first woman to join the esteemed Harvard Law Review.

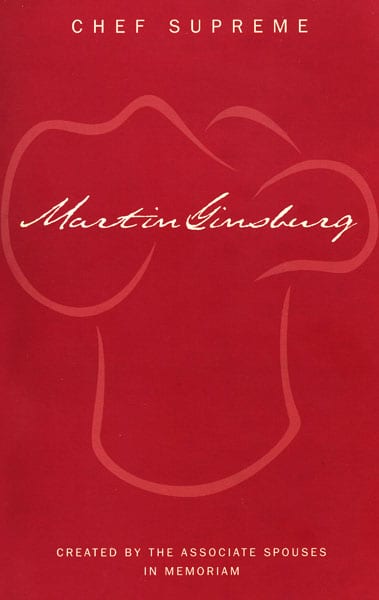

In the 1970s, Marty took over all family affairs—notoriously, cooking—while Ruth established the Women’s Rights Project of the American Civil Liberties Union, under which she argued six gender-equality cases in front of the U.S. Supreme Court.

“I have been supportive of my wife since the beginning of time, and she has been supportive of me,” Marty told The New York Times upon Ruth’s Supreme Court nomination in 1993. “It’s not sacrifice; it’s family.”

Marty passed away in 2010. I hope he and Ruth are dancing together in a fancy hotel somewhere, dressed to the nines, sipping cocktails to live jazz.

Rest easy, RBG.