On June 28, 1895, the wedding announcement for the marriage of Ida B. Wells appeared on the front page of The New York Times in a single paragraph at the bottom of the page. Though small, its significance was extraordinary: Wells was African American, born into slavery in Mississippi in 1862, three years before the end of the Civil War. But Wells led a remarkable—and often overlooked—life in the years following the war.

With the end of the Civil War came segregation, as whites in the South sought to keep themselves separate from freed slaves who were now trying to forge a life in an unfamiliar society. In 1877, the Supreme Court passed the Jim Crow laws, which legalized segregation, first on public transportation. In 1884, more than 70 years before Rosa Parks refused to give up her seat to a white man on a bus, Wells refused to move from a whites-only train car, and was dragged off and arrested. She sued the railroad, winning $500 in circuit court, and took her case all the way to the Tennessee Supreme Court, but lost.

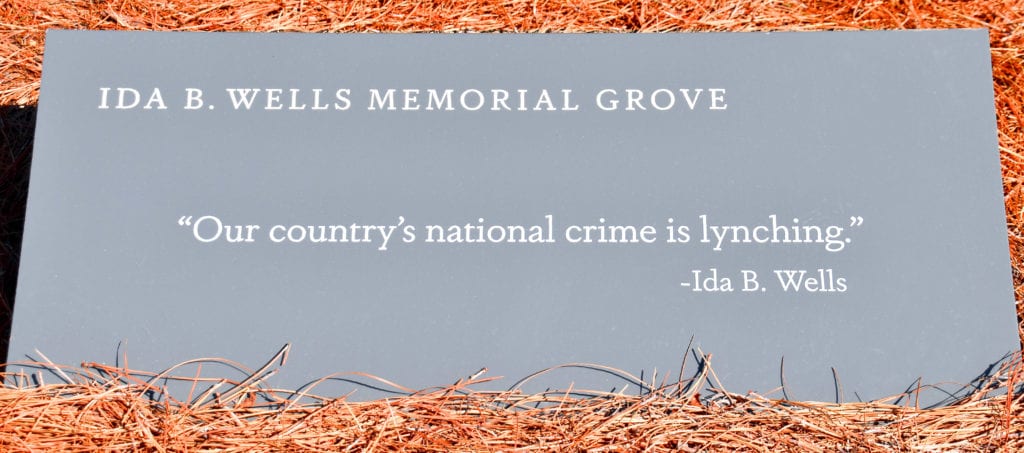

As a journalist, Wells spent the next several years writing about race and politics in the South for black newspapers, using the moniker “lola.” She eventually became an owner of the Memphis Free Speech and Headlight, and later, of the Free Speech. Wells’s anti-lynching crusade began in 1891, when her friend, a black grocery store owner in Memphis, was killed by a mob after a white store owner became angry about the success of his business.

This led Wells to write a series of investigative articles on post-Civil War lynchings in the South. She traveled throughout the northern states on lecture tours to mobilize public opinion against lynching. While in New York, a mob, angry from a recent article she’d written, burned her newspaper’s office and threatened her life if she ever returned to Memphis.

Wells stayed in the North, and in 1893 wrote “The Reason Why the Colored American Is Not in the World’s Columbian Exposition,” in response to the ban on African American exhibitors at the 1893 World’s Columbian Exposition. The pamphlet’s publication and circulation were funded by her close friend, abolitionist and freed slave Frederick Douglas, and Ferdinand Lee Barnett, a lawyer and founding editor of The Chicago Conservator.

After Wells moved to Chicago in 1894, she opened a black settlement house offering housing and social services to African Americans moving North. There, Barnett pursued Wells, largely due to the mutual support of each other’s careers (many historians consider him a feminist). Before they married, Wells purchased his stake in the Conservator and became the manager and co-editor, while Barnett focused on his legal career. (In 1896, he became the first black person to serve as Illinois’s Assistant State’s Attorney.)

Their wedding—which had to be postponed three times due to Wells’s bustling schedule—was held on Thursday, June 27, 1895 at 8 p.m. in Chicago’s Bethel Church. The invitations were sent on stationary bearing the name of her women’s club, noting her as president. Wells’s bridesmaids wore lemon crepe dresses and slippers, and she wore a white satin trained gown trimmed with orange blossoms. Both white and black newspapers covered the wedding.

In her autobiography, Wells wrote, “The interest of the public in the affair seemed to be so great that not only was the church filled to overflowing, but the streets surrounding the church were so packed with humanity that it was almost impossible for the carriage bearing the wedding bridal party to reach the church door.”

The newlyweds honeymooned for a weekend, and when she returned to Chicago, rather than take up an idle lifestyle, Wells wrote, “I decided to continue work as a journalist, for this was my first, and might be said, my only love.”

In 1896, she formed the National Association of Colored Women. In 1908, she helped found the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP). Just before her death in 1931, Wells made a bid for the Illinois State Senate. While unsuccessful, it paved the way for woman candidates in the years following.

Today, Wells and Barnett’s home on the South Side is a designated Chicago Landmark and listed on the National Register of Historic Places. Her legacy was honored in 2018, when the city renamed Congress Parkway to Ida B. Wells Drive, making it the first downtown street named for a woman of color.